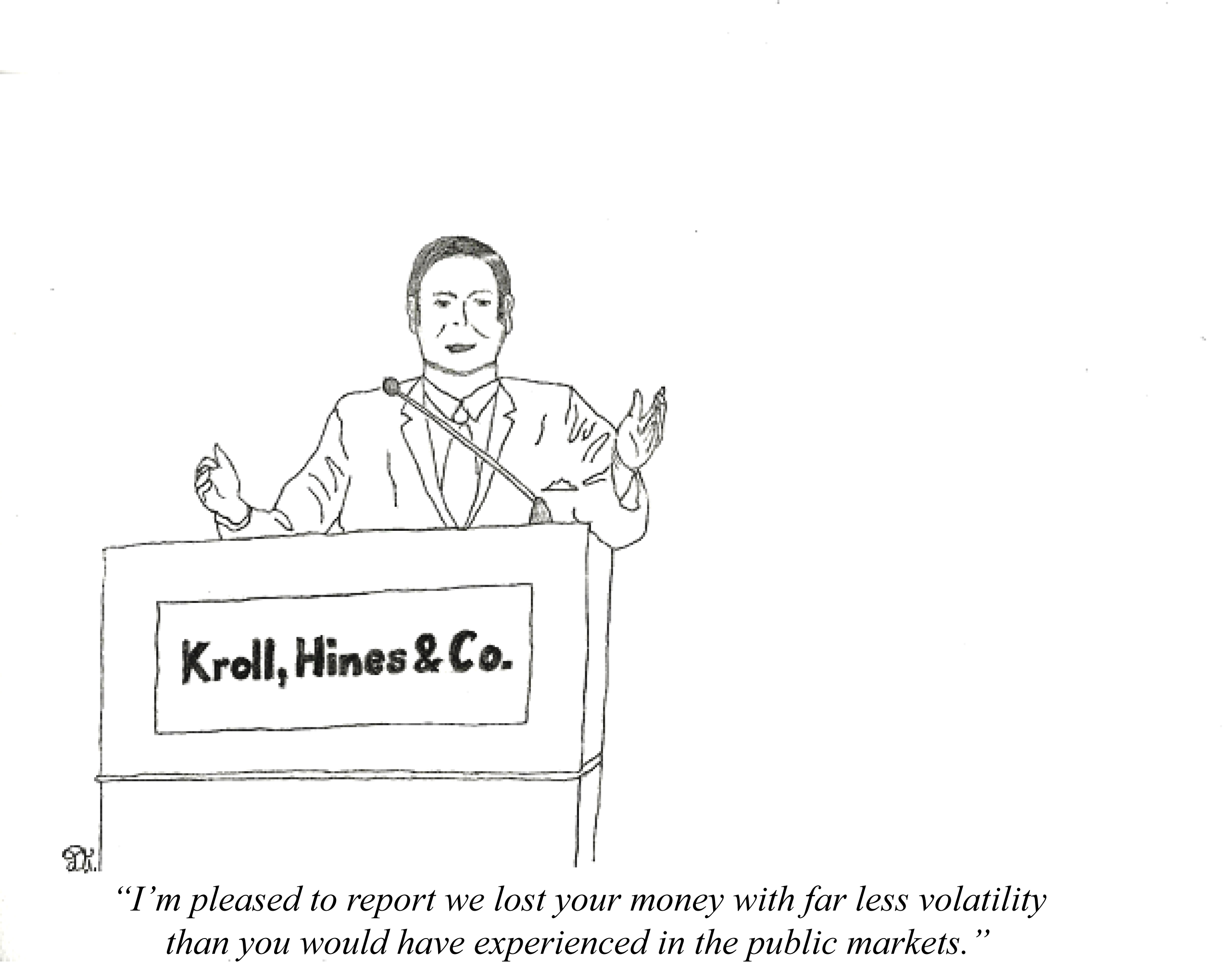

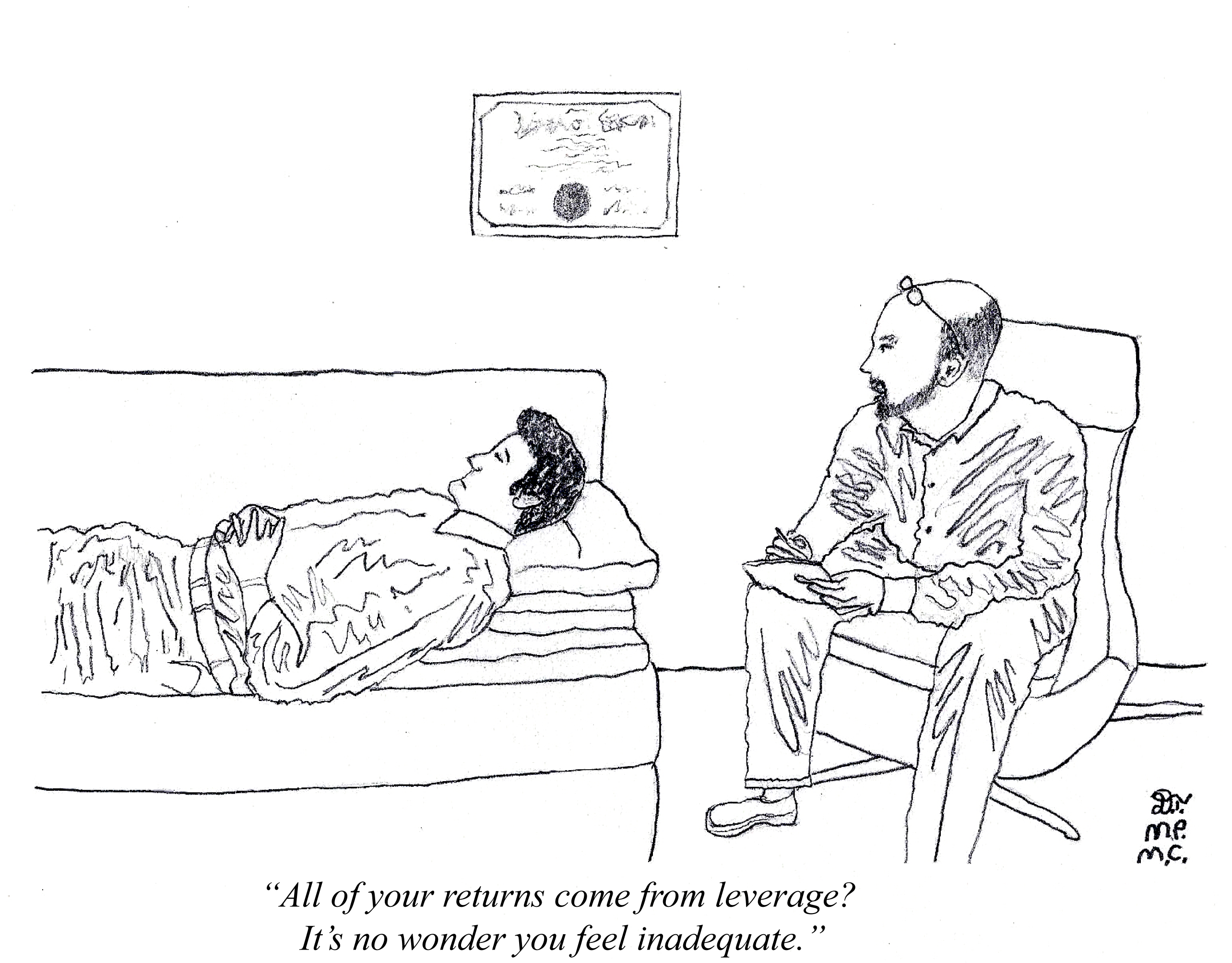

For the better part of a decade, institutional investors have redeemed capital from active strategies and dumped it into Private Equity (PE). What’s the benefit of PE for allocators? You get to have levered equity returns without the volatility of actually owning public equities. Unlike stocks that often fluctuate wildly, PE is marked-to-model (M-T-M), hence quarterly volatility is minimal. Then, when there’s a liquidity event, you get to see how well you did. Or at least, that was the theory. However, by the time of the liquidity event, usually someone else is in charge of the position. Meanwhile, you’ve used the nice smooth M-T-M to earn yourself a bunch of bonuses and maybe even a promotion to somewhere else that’s ring-fenced from your allocation decisions at your prior job. In many ways, the funds and the allocators themselves are both incentivized to mark the numbers higher and hope that they’re proven right.

Over the past year, I have been highly critical of the Ponzi Sector. You have businesses with no hope of ever showing profits, focused on using VC capital to create revenue growth in the hope of an IPO. As the IPO window has now closed, these companies are in something of a bind; if they slow growth to reduce losses, they become no-growth incinerators of capital and if they keep going, they may find that they cannot make payroll one day—remember WeWork? You also have the issue of the VCs themselves; do they really want to fund this thing anymore? A year ago, they knew they could put money in at a $1 billion value because Softbank would do the $10 billion round and then they could dump it on retail. Even if it was a down-round from Softbank, who cared, they set the mark and everyone else felt like they got a bargain in the IPO. However, times have changed; who would still value a fake business at $1 billion if there was no hope of an IPO in the near future? These sorts of little dramas are getting sorted out behind closed doors and not a day goes by without us hearing of another round of VC unicorn layoffs. As the VC ecosystem has a slow-motion coronary, it’s worth asking what else looks like VC; where else can you mark-up your friend’s portfolio if he’s willing to mark-up yours.

Well, PE sure looks similar—fake marks, unrealistic expectations and a lot of incentive to ignore reality in the hope of bluffing your way into an IPO. In VC, this all ended when Uber (UBER – USA) and Lyft (LYFT – USA) both had down-rounds, followed by WeWork failing to raise capital at any price. Since then, we’ve seen failures by many smaller companies like Casper (CSPR – USA), which serve to remind equity investors why they shouldn’t buy VC IPOs. However, PE was notably absent in this drama until recently. Is the bankruptcy of EnCap’s Southland Royalty, PE’s very own WeWork moment?

I’m not trying to pick on EnCap; I’m sure they tried their best. That doesn’t change the fact that they marked their Southland asset at $773.7 million at the end of Q3/2019 and then marked it at zero a few months later. Having been in the investing world, I can commiserate with EnCap. Sometimes it’s really hard to tell what something’s worth. However, this isn’t Schrodinger’s cat; it’s either a healthy business or hurtling towards bankruptcy. It can’t be both and it should have been aggressively impaired heading into bankruptcy.

Interestingly, while EnCap gets the opprobrium for being first, they certainly won’t be the last or even the largest to report similar drastic write-downs. Last week I had lunch with a friend who’s rather high up in the PE world. He repeatedly made the point that many of the marks are simply wrong and a surprisingly large number of mid-decade vintage deals are going sour at an alarming rate. I suspect there will be many more surprises coming—the sort of multi-billion-dollar write-offs that will forever change PE’s image of low-volatility capital allocators.

The odd thing is that allocators invested in PE due to its Madoff-like volatility profile. Ironically, they also forgot that this led to a collapse at the end. If last cycle’s crisis was caused by Madoff’s admission that it was all fake, will this cycle be bookended by PE’s similar admission?

The money seeking low volatility will likely be surprised and then revulsed simultaneously. So, what happens to all the PE deals when the current funds expire? It was always assumed that Vehicle IV would purchase assets from Vehicle III (a Ponzi Scheme in its own right). Without capital for a new fund, you need to have an actual third-party monetization event—either a sale to a strategic or an IPO. My hunch is that these valuations undershoot drastically. My friend was joking that most deals he’s looked at lately aren’t even worth the debt associated with them—there’s literally zero equity left and the marks are in fantasy-land. I suspect that we’ll soon learn that the last decade of PE was little more than an exercise in valuation gamesmanship and fee generation for everyone involved (GPs and allocators are equally guilty here).

The past few years have been unusual in that private businesses routinely traded at premiums to public businesses. Any student of common sense would understand that immediate liquidity and broad access to capital ought to mean that public companies deserved a premium multiple—even after the added costs of being public. The fact that this wasn’t happening ought to have been a clue that something nefarious was going on. It only lasted this long because an epic liquidity bubble coupled with allocator’s desire to never re-live 2008’s volatility, pushed them into chasing Ponzi Schemes in all their varied forms. The VC bubble burst the day that WeWork went from being worth tens of billions to almost missing payroll. Something very similar seems to be happening in PE as we speak and Southland Royalty is the canary in this coal mine.

What are the investment implications? When I started in the investment business, companies went public to raise growth capital. For the past decade, this has been unnecessary and counter-productive. Why expose yourself to valuation by the masses, when you can massage numbers and raise money privately—often at a premium valuation? I suspect that over the next few years, this trend will revert to historic form and companies will once again need the public markets to raise capital—especially as their PE shareholders are forced down the IPO road as a form of liquidity. Oddly, this will be at precisely the moment when the smallest percentage of capital in financial history is controlled by active managers. Could this be an unusually attractive moment for active managers to buy into IPOs from distressed sellers? The more fraud that we ultimately witness in PE, the more likely it is that these liquidity events will have the sorts of stigmas associated with them that lead to incredible prices. Stay tuned; PE and VC controlled the past decade due to asset allocators with multi-decade duration mismatches, going out of their way to avoid monthly volatility—if that sounds illogical to you, it’s because most allocators are human and respond to social pressure in their tight-knit finance communities. They do what their friends are doing, as career risk is just too great—especially when it isn’t even their money when it all blows up.

The twin VC and PE bubbles are now unraveling—rapidly. I have a feeling that the next few years will be a golden age for active management as PE aggressively disgorges tarnished assets back into the public markets often at pennies on the dollar. For active portfolio managers, this will be the sort of thing that fortunes are made of. PE is having its WeWork moment as we speak—investors will lose fortunes from their goal of dampening volatility. I don’t think they’ll then hazard back into PE for decades. I can’t wait for the bargains that are created…

If you enjoyed this post, subscribe for more at https://adventuresincapitalism.com

For The 10th Anniversary of AiC, Let’s Visit The Douro Valley

February 13, 2020Extreme Complacency…

February 24, 2020Is PE Having Its WeWork Moment…???

For the better part of a decade, institutional investors have redeemed capital from active strategies and dumped it into Private Equity (PE). What’s the benefit of PE for allocators? You get to have levered equity returns without the volatility of actually owning public equities. Unlike stocks that often fluctuate wildly, PE is marked-to-model (M-T-M), hence quarterly volatility is minimal. Then, when there’s a liquidity event, you get to see how well you did. Or at least, that was the theory. However, by the time of the liquidity event, usually someone else is in charge of the position. Meanwhile, you’ve used the nice smooth M-T-M to earn yourself a bunch of bonuses and maybe even a promotion to somewhere else that’s ring-fenced from your allocation decisions at your prior job. In many ways, the funds and the allocators themselves are both incentivized to mark the numbers higher and hope that they’re proven right.

Over the past year, I have been highly critical of the Ponzi Sector. You have businesses with no hope of ever showing profits, focused on using VC capital to create revenue growth in the hope of an IPO. As the IPO window has now closed, these companies are in something of a bind; if they slow growth to reduce losses, they become no-growth incinerators of capital and if they keep going, they may find that they cannot make payroll one day—remember WeWork? You also have the issue of the VCs themselves; do they really want to fund this thing anymore? A year ago, they knew they could put money in at a $1 billion value because Softbank would do the $10 billion round and then they could dump it on retail. Even if it was a down-round from Softbank, who cared, they set the mark and everyone else felt like they got a bargain in the IPO. However, times have changed; who would still value a fake business at $1 billion if there was no hope of an IPO in the near future? These sorts of little dramas are getting sorted out behind closed doors and not a day goes by without us hearing of another round of VC unicorn layoffs. As the VC ecosystem has a slow-motion coronary, it’s worth asking what else looks like VC; where else can you mark-up your friend’s portfolio if he’s willing to mark-up yours.

Well, PE sure looks similar—fake marks, unrealistic expectations and a lot of incentive to ignore reality in the hope of bluffing your way into an IPO. In VC, this all ended when Uber (UBER – USA) and Lyft (LYFT – USA) both had down-rounds, followed by WeWork failing to raise capital at any price. Since then, we’ve seen failures by many smaller companies like Casper (CSPR – USA), which serve to remind equity investors why they shouldn’t buy VC IPOs. However, PE was notably absent in this drama until recently. Is the bankruptcy of EnCap’s Southland Royalty, PE’s very own WeWork moment?

I’m not trying to pick on EnCap; I’m sure they tried their best. That doesn’t change the fact that they marked their Southland asset at $773.7 million at the end of Q3/2019 and then marked it at zero a few months later. Having been in the investing world, I can commiserate with EnCap. Sometimes it’s really hard to tell what something’s worth. However, this isn’t Schrodinger’s cat; it’s either a healthy business or hurtling towards bankruptcy. It can’t be both and it should have been aggressively impaired heading into bankruptcy.

Interestingly, while EnCap gets the opprobrium for being first, they certainly won’t be the last or even the largest to report similar drastic write-downs. Last week I had lunch with a friend who’s rather high up in the PE world. He repeatedly made the point that many of the marks are simply wrong and a surprisingly large number of mid-decade vintage deals are going sour at an alarming rate. I suspect there will be many more surprises coming—the sort of multi-billion-dollar write-offs that will forever change PE’s image of low-volatility capital allocators.

The odd thing is that allocators invested in PE due to its Madoff-like volatility profile. Ironically, they also forgot that this led to a collapse at the end. If last cycle’s crisis was caused by Madoff’s admission that it was all fake, will this cycle be bookended by PE’s similar admission?

The money seeking low volatility will likely be surprised and then revulsed simultaneously. So, what happens to all the PE deals when the current funds expire? It was always assumed that Vehicle IV would purchase assets from Vehicle III (a Ponzi Scheme in its own right). Without capital for a new fund, you need to have an actual third-party monetization event—either a sale to a strategic or an IPO. My hunch is that these valuations undershoot drastically. My friend was joking that most deals he’s looked at lately aren’t even worth the debt associated with them—there’s literally zero equity left and the marks are in fantasy-land. I suspect that we’ll soon learn that the last decade of PE was little more than an exercise in valuation gamesmanship and fee generation for everyone involved (GPs and allocators are equally guilty here).

The past few years have been unusual in that private businesses routinely traded at premiums to public businesses. Any student of common sense would understand that immediate liquidity and broad access to capital ought to mean that public companies deserved a premium multiple—even after the added costs of being public. The fact that this wasn’t happening ought to have been a clue that something nefarious was going on. It only lasted this long because an epic liquidity bubble coupled with allocator’s desire to never re-live 2008’s volatility, pushed them into chasing Ponzi Schemes in all their varied forms. The VC bubble burst the day that WeWork went from being worth tens of billions to almost missing payroll. Something very similar seems to be happening in PE as we speak and Southland Royalty is the canary in this coal mine.

What are the investment implications? When I started in the investment business, companies went public to raise growth capital. For the past decade, this has been unnecessary and counter-productive. Why expose yourself to valuation by the masses, when you can massage numbers and raise money privately—often at a premium valuation? I suspect that over the next few years, this trend will revert to historic form and companies will once again need the public markets to raise capital—especially as their PE shareholders are forced down the IPO road as a form of liquidity. Oddly, this will be at precisely the moment when the smallest percentage of capital in financial history is controlled by active managers. Could this be an unusually attractive moment for active managers to buy into IPOs from distressed sellers? The more fraud that we ultimately witness in PE, the more likely it is that these liquidity events will have the sorts of stigmas associated with them that lead to incredible prices. Stay tuned; PE and VC controlled the past decade due to asset allocators with multi-decade duration mismatches, going out of their way to avoid monthly volatility—if that sounds illogical to you, it’s because most allocators are human and respond to social pressure in their tight-knit finance communities. They do what their friends are doing, as career risk is just too great—especially when it isn’t even their money when it all blows up.

The twin VC and PE bubbles are now unraveling—rapidly. I have a feeling that the next few years will be a golden age for active management as PE aggressively disgorges tarnished assets back into the public markets often at pennies on the dollar. For active portfolio managers, this will be the sort of thing that fortunes are made of. PE is having its WeWork moment as we speak—investors will lose fortunes from their goal of dampening volatility. I don’t think they’ll then hazard back into PE for decades. I can’t wait for the bargains that are created…

If you enjoyed this post, subscribe for more at https://adventuresincapitalism.com